A famous song from the early 20th century starts with the line “Though April showers may come your way, they bring the flowers that bloom in May.” April is typically not a great month for deep sky astrophotography, .so when May comes around and some of us astrophotographers can’t wait to get back to photographing the stars, we sometimes photograph another star: our own.

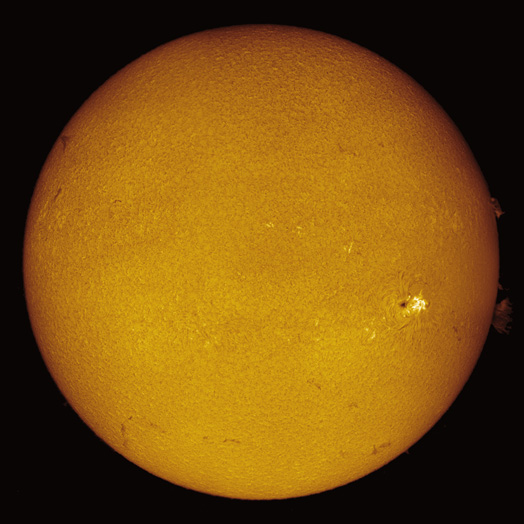

It turns out that our star is extremely photogenic, and there are some who make images of little else in the sky. It’s tricky to get a good image of the sun and this one, while adequate, is nowhere near the fabulous images I’ve seen from seasoned practitioners of solar photography. Even so, there’s plenty to see here.

The sun is, of course, literally blindingly brilliant. To look directly at it for any length of time risks permanent damage to your retina. The same holds true of cameras. To photograph the sun, its brightness must be reduced by a factor of a million or more. Even then, it can be a relatively featureless disk, with a few sunspots interrupting its seemingly smooth “surface.” When all but the light of Hydrogen is eliminated, though, we can see the true textures and features of the light-emitting surface of the sun.

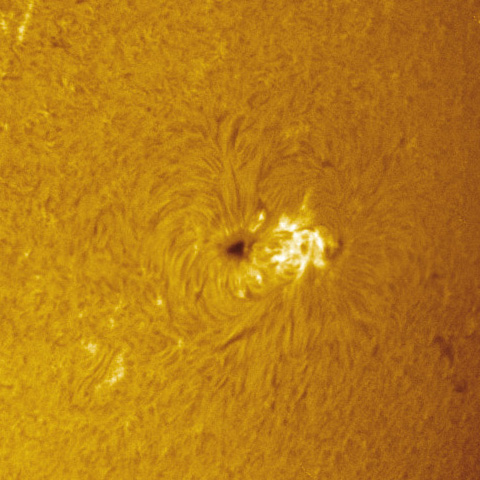

In this image, most notably, we see a bright region to the lower right. This is called an “Active Region,” primarily because there’s a LOT going on in things like this. The brightest parts are extremely hot, much hotter than the normal temperature of the surface, made so by the intense twisting of the magnetic field in the area. This magnetic field seems to emanate from the dark sunspot and its associated bright region, organizing the otherwise random texture of the sun’s gasses. The magnetic field lines are easily traceable here. This region is a good candidate for a solar flare. If the magnetic field gets twisted enough, it could produce a major flare, disrupting radio and satellite communications, power grids, and producing displays of northern lights.

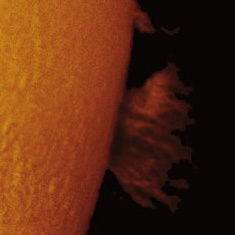

Solar prominences are usually considerably more benign. These clouds of glowing gasses occur in all kinds of shapes and sizes. Most are rather small, but some gigantic ones have been photographed over the years. A quick google will turn up some spectacular examples. There are a couple of them at the right edge of this image. These are easy to see against the dark background of space, but they’re not the only ones present in the image. The many dark ribbons crisscrossing the surface are all prominences; they’re just not as plain as the ones at the edge. Their dark appearance tells us they’re cooler than the surface.

One great thing about photographing the sun is that you can do it during the day. Long sleepless nights are not needed, and in fact, are not even useful since you obviously can’t photograph the sun at night. (You’d be surprised at how often I’m asked why when I say that.) The next time you glance up at the sun, keep in mind that there’s a lot going on there you can’t see!